Sufism in a global world

Author: Ingo Taleb Rashid

The German-Iraqi master of Sufism talks about renewing the tradition. Opening to other spiritual paths, Sufi dances and chants, God, clarity of direction, the path to inner peace, non-conformist mysticism. The role of the body in spirituality, art, and how to come to oneself through meditation on the names of God.

SUFISM TRADITION

Tattva Viveka: Ingo, your mother is German, your father is Iraqi, and you studied theater, political science, communication, and Semitic languages at Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. You are Sheikh of the Naqshbandi Rashidiya Tariqa and now also head of this Sufi tradition. You also founded the Movement Concept, which we will talk about later. Also you are a teacher of the Japanese martial art Bujinkan Budo Taijutsu. How did this come about for you?

Ingo Talib Rashid: I am overwhelmed by the details you have found out. I was born in Munich. My father was Iraqi from Baghdad, as I mentioned, and my mother was German-Polish. I grew up in Baghdad for most of my preschool years. My father was Sheikh of the Naqshbandi Rashidiya Tariqa, as was my grandfather, his father and my ancestors way back in the past. So I was born into a Sufi lineage. Sometime between the ages of five and six, I was initiated into that lineage for the first time, along with my grandfather, who took me to a firewalk. That was the entry into formal training within this Sufi tradition.

My grandfather, my father, and also my mother felt at some point that I needed to renew the tradition. The tradition has to adapt according to each generation to the appropriate time in which the leader of the tradition is working. You can’t work the way you did 500 years ago in Baghdad. Therefore, I should have contact with martial arts training from childhood.

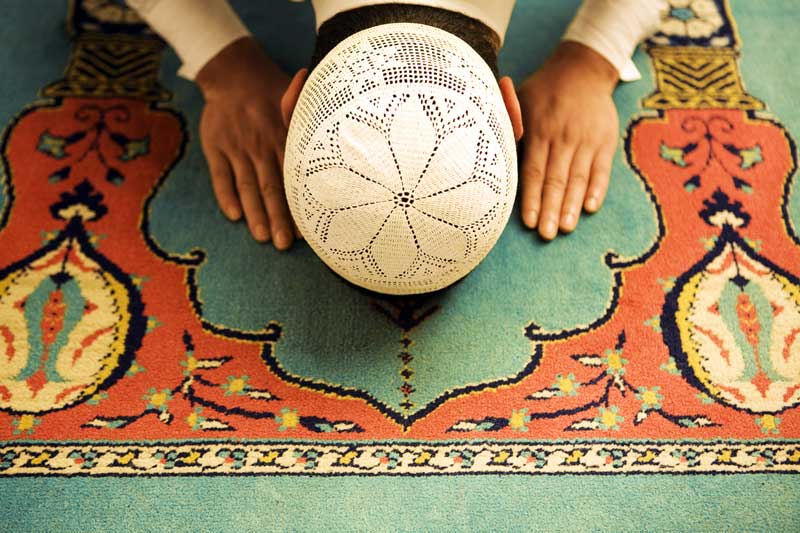

Mystical freedom© Adobe Photostock

Mystical freedom© Adobe Photostock

The Sufi tradition I was born into is a house within the well-known Naqshbandi Tariqa, known in the West as ‘the silent Sufis’. Sufi traditions are not centrally organized, such as the Catholic Church. There is not one Sheikh in the world who is responsible for all Sufis, nor is there one Sheikh for all Naqshbandi. Instead, there are very many different Naqshbandi lineages that operate completely independently of each other. One of my ancestors founded one of them: Sheikh Abu Bakar An-Naqshband, who came to Baghdad from Central Asia via Turkey.

This tradition brought a lot of sacred dances from Central Asia.

FAITH AND TRADITION IN SUFISM

TV: So you have gained an insight into an incredible number of world regions and also into the spiritual or cultural structures of these traditions, and yet you are mainly at home in the Sufi faith?

Rashid: I wouldn’t call it a faith. It’s more of a practice path. An important aspect of this practice path is religio, the Latin religio as a reconnection to the divine source, whatever you call it: Allah, God, the divine.

The translation ‘the divine’ is perhaps Allah at its best, because it is not so personified and less gendered.

Very important is the aspect of practice. In my view or the view of our tariqa, the specific religious affiliation of the practitioner is secondary. Some practitioners are Muslims, unlike others, who do not belong to any specific religion. We have practitioners who are Orthodox Christians, Jews, etc. I myself would say that the tradition has opened up for me. The Sufi tradition is my base from which I come, but I have been fortunate to learn about many other traditions and to experience the validity, the validity, the value of these other traditions.

THE CONNECTION BETWEEN DANCE AND FAITH

TV: Yes, you have this dance school. So that we stay with Islam and Sufism: I would like to address the importance of the body within a spiritual way of life. You point out that it is an important element. Also the name of your school El Haddawi says that. What does this name mean and what do body, soul and spirit have to do with each other in your tradition?

Rashid: El Haddawi could mean ‘drunk with the divine’ or ‘presence,’ presentness. This presence includes inhabiting one’s own body, being able to perceive and feel oneself in one’s own body, in one’s own body. We say in Sufism that the body is a temple.

The body is like a house of prayer that we have to pay attention to in order to come into presence or to begin the spiritual path of practice.

That’s why in our tradition – it’s called Haraka al Muqaddas – there are sacred movements, sacred dances, and sacred steps that train those aspects of physicality. We consider body, mind and spirit as one here on this earth, we don’t separate that. We are in the world as one.

Even if we are just working spiritually and sitting down to meditate, that is a physical process.

Dance© pexels

TV: So it’s an elaborate system of different steps and dance movements that each do something of their own. You also have vocal and breathing techniques, do I see that right?

Rashid: Naturally, yes.

TV: So you also sing?

Rashid: Yes, for one thing, we recite the Quran in a set form, called Tadschwid, which is a style of recitation. I don’t just read it out, I recite it in a very specific form. In addition, we also practice the Dhikr Allah, the remembrance of the divine. Here breathing, voice, rhythm and movement are coordinated and combined. Just like the sacred steps, naturally certain dhikr have their own effects. The most famous is La Ilaha il Allah – there is no reality except the source. When practiced in a certain way, with a certain breathing technique, in the community, it exerts a certain effect on the community and the individual.

Sufism in a global world© Adobe Photostock

TV: I’ll take up the keyword art in a moment, because you emphasize the connection of art with spirituality. Can you say something more about that?

Rashid: Art is a beautiful form to live, to represent, to express spirituality, indeed to the delight of everyone involved. That doesn’t mean that a dance theater piece is all peace, joy, pancakes. We have realized productions that address strong social issues and lead the spectator through difficult movements. But nevertheless they offer a way to express humanity, and that without lecturing, with a book in hand.

TV: In this connection of art, body and spirituality, you also developed the ‘Movement Concept’?

Rashid: Yes, it is the sum of my experiences with Sufism, with Western theater, with classical ballet, modern dance. Also martial arts from Japan, Capoeira from Brazil, then the study of anatomy, of meditation, of acting. I tried to integrate that, as best I could, into a living system called Movement Concept.

TV: Finally, would you like to perhaps give us a message for people on how they can engage with Islam, or come to terms with it? What plea for the beauty of Islam would you give to Christian-based people living in the West and in Europe?

Rashid: Encounter. Real encounter on all levels. Encounters with Islamic people, encounters with Islamic literature, Islamic music, with Islamic countries. As everywhere, one will have good and bad experiences and should not look for the most orthodox voices in the search for encounters. One should dare to travel this new territory with common sense. Then you will get something out of it and the experience, the moments, the knowledge is the reward.

About the author

About the author

Ingo Taleb Rashid, M. A., Sheikh and head of the Naqshbandi Rashidiya Sufi tradition, founder of Movement Concept®, choreographer and director. Teacher of the traditional Japanese martial art Ninpo. Artistic director of El Haddawi Dance Company and dance theater school. Choreographer of the musical “Peace Child”, one of the first theater productions in Israel in which Jewish and Arab children participated together.

Website: www.elhaddawi.de

This article was originally published on the German Homepage of Tattva Viveka: Mystische Freiheit