The Mystic Core of Art

Author: Ronald Engert

Category: Art, Music & Literature

Issue No: 93

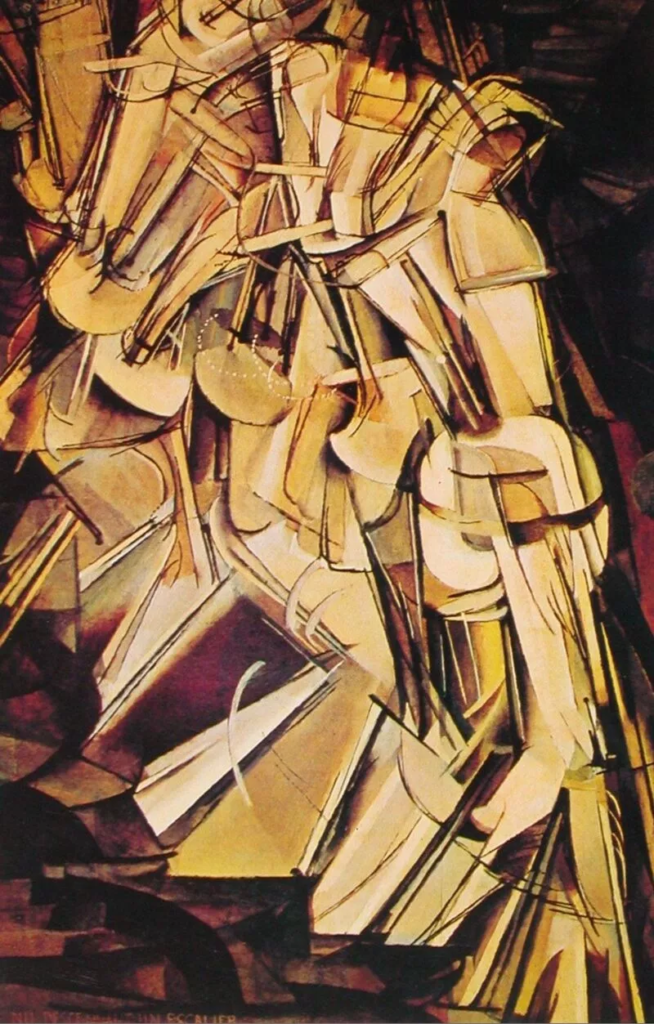

Art is not just a craft skill, but a deep exploration of reality, a radical and uncompromising stocktaking, an inner struggle of the artist to find the right form that speaks to the soul of the beholder. Genuine art is revolutionary and breaks the mould of the known. Art is seeing anew. It has this in common with spiritual awakening, the mystical arrival in the here and now. André Breton, Wassily Kandinsky and Walter Benjamin are called upon here as its witnesses.

“To create a work of art,

is to create the world.”

Wassily Kandinsky (1866-1944)

“Saint-Pol-Roux, when he lay down to sleep in the morning, put a sign on his door: ‘Le poète travaille – the artist works’. Breton notes: ‘Quiet. I want to pass through where no one has passed through yet, still! – After them, dearest language.’ That takes precedence.”[1]

An essential element of art is to make visible what has never been seen before or to make audible what has never been heard before – and to free oneself from preconceived judgements and ideas. That is why Breton wants to go through where no one has gone before. And Saint-Pol-Roux wants to sleep, because then he dives into his unconscious.

Surrealism was not just one art form (surrealism) among many, but an expansion of consciousness beyond everyday consciousness into the spiritual or – as we would say today – into the spiritual. Surrealism was about transcending the ego: “In the world structure, the dream loosens individuality like a hollow tooth.”[2] André Breton gives the following definition in his first Surrealist manifesto: “Pure psychic automatism by which one seeks to express orally or in writing or in any other way the real course of thought. Dictation of thought without any control by reason, beyond any aesthetic or ethical consideration.”[3] This expresses very well the surrealist principle: an immediate perception without rational considerations, without aesthetic criteria, without ethical judgements, indeed without intention, because we are always separated from what we want by time.

Seeing in real time

Benjamin subtitled his great essay on Surrealism from 1929: “The last snapshot of the European intelligentsia”. This can mean two things: The European intelligentsia is the object and the essay is the last shot of it, or: The European intelligentsia is the subject and takes a last snapshot.

In fact, surrealism could be understood as this subject taking a snapshot of reality for the last time in history. This would mean that everything that comes after is no longer a perception of reality. In fact, the naive image theory was recognized as obsolete in philosophy, in art and also in physics at the beginning of the 20th century. It was realized that what we see is not what is really out there. Rather, we construct a kind of conditional reality through our perception and mind that is subjective. In philosophy, this direction is called “constructivism” and is the main theorem of so-called postmodernism. The general uncertainty led to constructivism addressing the question of whether there is anything out there at all. Since that time, the possibility that one can perceive reality objectively has been denied. Since that time, everyone has lived in their own subjective universe, and the question of what reality – or even truth – is, is considered unanswerable. That is why Benjamin writes of this last snapshot.

The naïve perception of reality, as it were like a timeless image of a metaphysical truth, was no longer possible at that time for the first time,

because the world was becoming increasingly complex, and the breakneck speed of information quanta of mechanization and mass society turned perception into a piecemeal process. It was no longer possible to keep track of everything.

Surrealism could no longer provide this timeless image, but it could do something else: a recording of the moment. A single quantum of information of reality – the moment – was still represented by the surrealists. There was still an object in art. Only then did this end, and art seemingly went entirely into a play with form and colour, into abstraction. The content dissolved, not only in the visual arts, but also in avant-garde literature. In post-structuralism, the meaninglessness of the world is still often asserted today.

These are excerpts from the article.

Why Wassily Kandinsky described abstract art as mystical and to what extent surrealism depicts reality, you can read in the complete article published in Tattva Viveka 93. You can also download it individually as an ePaper for € 2.00 (pdf, 8 pages).

About the author

Tattva Viveka Editor-in-Chief Ronald Engert

Ronald Engert, born 1961. 1982-88 studied German, Romance languages and literature and philosophy, 1994-96 Indology and Religious Studies at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt/M. 1994 co-founded the journal Tattva Viveka, since 1996 publisher and editor-in-chief. 2015-22 Studied Cultural Studies at the Humboldt University of Berlin. 2022 Master’s thesis on “Mysticism of Language”. Author of “Gut, dass es mich gibt. Diary of a Recovery” and “The Absolute Place. Philosophy of the Subject”.

Blog: ronaldengert.com

Footnotes:

[1] Walter Benjamin: Der Sürrealismus. The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia, Collected Writings, Vol. II, pp. 296f.

[2] Benjamin, ibid., p. 297.

[3] André Breton: First Manifesto of Surrealism, in: Als die Surrealisten noch recht hatten. Texte und Dokumente, Hofheim im Taunus 1983, p. 36 [first edition 1924].

This article appeared originally on the German Homepage of Tattva Viveka: Die Existenz ist anderswo