The three dimensions of the soul

Author: Dr. Jens Heisterkamp

Issue No: 95

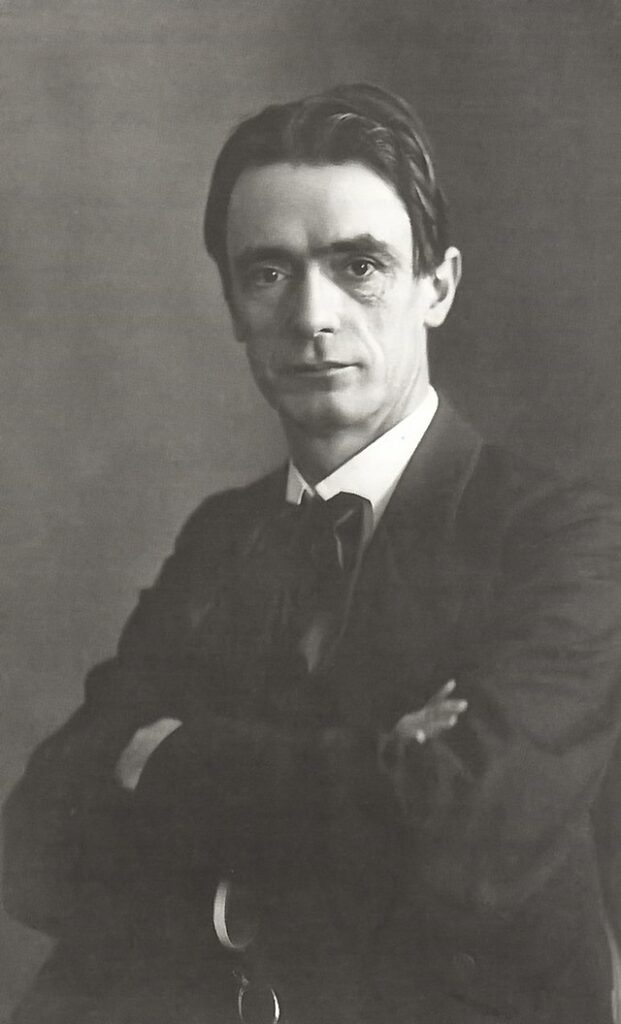

As the founder of anthroposophy, Rudolf Steiner developed a new understanding of the concept of the soul. His understanding was mainly influenced by the philosophy of Aristotle and Brentano. He distinguished between the feeling soul, the understanding soul and the consciousness soul, which the human being experiences in his earthly existence.

The 20th century was the century of the rediscovery of the soul. Sigmund Freud, Edmund Husserl, C. G. Jung and many others began, often enough outside the mainstream, to engage anew with the phenomena of the soul. Particularly since the second half of the 20th century, this also gave rise to a number of new therapeutic approaches. In the academic-scientific world, however, the term “soul” is hardly ever used. Yet the term still has a magic. Many people feel that something lies here that has to do with the deeper side of themselves.

A little-known approach to understanding the soul goes back to Rudolf Steiner, the founder of anthroposophy (1861-1925). There is even a connecting moment of his thinking with that of other important pioneers of the soul. In 1918 Steiner published his book “Von Seelenrätseln”. He dedicated it to the philosopher Franz Brentano, who had died shortly before, was one of his teachers during Steiner’s years of study in Vienna and whom he admired throughout his life. It is interesting to note who else, apart from Steiner, had attended Brentano’s lectures in Vienna at the end of the 19th century: none other than Sigmund Freud and Edmund Husserl! So why did Steiner hold the philosopher Brentano in such high esteem?

Brentano based his work on Aristotelian philosophy. His aim was to find a philosophical-scientific approach to the soul, which in its own way was to be just as methodologically sound as the natural sciences, which were on the rise at the time – only that exact observation could not be directed outwards in the case of his object of research – after all, the soul is not an externally visible object – but inwards. On this introspective path, he sought a common essential feature of all phenomena of the soul. Brentano found it – and Steiner agreed with him here – in the structure of being directed towards something else. Soul, then, not as a kind of invisible object, but as a principle: for Brentano, all that is soulful is characterised by an “being-into-itself-beyond-itself”, the taking up of an external (or other) into an inner. Conversely, this inside always goes out of itself in its attention and activity. Brentano also used the term “intentional” for this. To put it another way: soul is a directed “in-between”.

Observing with Aristotle

Brentano thus took up a central motif of Aristotelian philosophy. This is important to note, since Steiner’s differentiated doctrine of the soul also has much in common with the great Greek (although – as will be seen later – it also took up affinities with the Eastern stream of wisdom). A doctrine of the soul in the line of Aristotle-Brentano-Steiner is more phenomenologically and concretely observationally oriented and in this respect differs from approaches that mean by “soul” a more indeterminate, somehow “deeper” connection (“The Soul of Nations”) or aim more metaphorically at a deeper being in human beings themselves. Ken Wilber, among others, seems to understand “soul” in the latter sense, which can lead to misunderstandings in dialogue with the European tradition.

Aristotle was the first thinker in the Occident to practise an approach to the soul that was no longer speculative but oriented towards phenomena. For him, soul is something that lives out between the body on the one hand and the spirit on the other (thus unlike Wilber, for whom “soul” represents the higher level – which in Europe from Aristotle to Hegel, however, is referred to as “spirit” – misunderstandings are pre-programmed here, as indicated). Unlike Plato, Aristotle no longer presupposed an essence of the soul (which already existed before birth), but described the structures and functions of the soul on the basis of concrete life. Aristotle refrained from making statements about whether there could be such a thing as an immortal soul, but simply described what he observed as characteristics of the soul.

If we attempt a simple definition, we can say, soul for Aristotle is the faculty by which a being becomes alive.

And aliveness is always movement. What he meant by this is best illustrated by a comparison with the world of minerals and stones. If you imagine a granite block on one side and a chamois in the mountains on the other, you will immediately notice that the stone has no movement of its own and thus no life. If the block has at some point detached itself from a mountain massif and rolled down to the valley, elements outside of itself are responsible for this: gravity and weathering forces give it its shape from the outside. The alpine climbing animal is different: something is at work within it that makes it a living being. The chamois moves out of inner drives, searches for food and can react to external impressions, for example by fleeing quickly if a walker comes too close.It also does not behave only mechanically (just as a boulder rolls downhill according to the laws of physics), but out of special instincts that are characteristic of its species.

The behaviour of the chamois (as well as that of all other animals) thus shows exactly those characteristics that Brentano described as essential for the soul: The animal intentionally directs itself towards its environment, it behaves out of an inner experience, it can give expression to its inner state (for example, fear). In other words, the chamois is a soulful being, whereas the stone reveals nothing to us that points to a (soulful) inner side.

Now Aristotle defined the soulish not by the concept of intentionality, but by the principle of an inherent life coming from within, which has also become clear in our example. But Aristotle also attributed this inherent power to plants. In what way? Well, to take the boulder as a comparison again: The stone, as we have seen, has no movement originating from within. It is only moved by external impulses. This is similar with plants, insofar as they cannot change their position themselves. However, through their gradual growth and above all through their change of form over time, they do show a form of inner-directed movement. That is to say: from a cherry carried by a bird to another place, where it excretes the kernel, a germ develops, then a small shoot, which in the course of the years branches out more and more and at some point finally becomes a flowering and fruiting tree itself. This movement follows the inner laws of the cherry tree. In this respect, Aristotle could speak of a “plant soul”, a principle of vitality that is inherent in the plant, although it does not yet have – according to Brentano’s criterion – intentionality, i.e. it does not have an experiencing inner being that is directed beyond itself. The “life-soul” follows, as it were, silently the laws of development given in the plant, without associating experiences with them. It also feels nothing of what is going on with it, because none of its life expressions point to an inner capacity. In addition, we know from biology that there must be a physical basis in evolution for the appearance of feeling and consciousness: a nervous system as a carrier of feeling and experience. This already exists in very low animal forms, but not in plants. In this respect, more recent views are also misleading which, for example, attribute to trees the ability to “learn” or to exchange “information”. These probably rather metaphorical ways of speaking are certainly suitable to evoke more empathy for vegetative life, but philosophically and scientifically they do not seem conclusive.

In contrast, the bird that “knows” according to its instincts that there are cherries in the cherry tree shows a real inner life (or consciousness); the blackbird can move intentionally towards a goal, the cherry tree.

And it also shows inner movements, such as fear when a cat approaches the tree, which it expresses through corresponding calls, or a kind of joy of life when it sings its song at sunrise and sunset. Animals, we can now further describe, are beings with souls, we could also say: beings that have a consciousness in which the outside world is reflected and with which they react to their outside world.

Now we can add a step: Animals like our blackbird are conscious, soulful beings that experience pain and joy. But they are not aware that they themselves are beings with souls. In this respect, they are more akin to plants, which simply follow the laws, drives and instincts that lie within them. Being aware of oneself – that only appears as a further quality with us humans, also from an evolutionary point of view. Of course, we humans also have an animal soul within us: we are also determined by instinctive experiences and reactions, by unconscious forms of behaviour that we do not (constantly) reflect upon. But with us, in all actions and interactions of the soul, the dimension can be added that we know about our experiencing and acting, that we become aware of the fact that it is we who are experiencing something here and who are thinking about something. Self-consciousness is added as a further level of the soul.

One soul, three dimensions

Now it is time to take stock and to link to the phenomena presented the basic concepts of the anthroposophical doctrine of the soul, which Steiner presented in his fundamental work “Theosophy”. What Aristotle still called the plant soul, Steiner does not see as a soul in the narrower sense, because it lacks the dimension of experiencing inwardness. Rather, he speaks here of the principle of the etheric, which determines the layer of the living, also in us humans. The actual soul begins in the animal kingdom. Steiner calls the first level of the soul in humans the sensory soul, a form of the soul that can receive and experience impressions.

While animals process their impressions according to the instincts that lie within them, that shape their species and are not reflected by themselves, in us humans there is the added ability to be able to make connections between the impressions of the outside world through thinking. We can also classify our own sensations and thoughts. It is our mind that determines our lives to a considerable extent, through inferences, reflections, forward planning and so on. But the mind also enables us to ask further questions about our humanity, to ask about the order of things, to think about the meaning of life and the world. All this takes place in the realm of the self-conscious soul, which Steiner also calls the mind soul.

Steiner now describes another level of the soul, which we have already touched on above: It is characterised by the faculty that we as human beings can also be conscious of our conscious (psychic) being: “I am conscious of myself and of my psychic experiences, I have the faculty of a consciousness reflected in itself.” This faculty also has to do with the phenomenon of the “I”, an identity that is conscious of itself, which does not show itself in any plant or animal, the ability to be able to say to oneself: “I am I.” Steiner calls this level of the soul the consciousness soul.

But it plays a role not only as a quality in our inner being, but also when it comes to connecting consciously with the world – through cognition. To really recognise something means not only to experience something of a thing, a being or a phenomenon mentally (the overwhelming starry sky), but to recognise something that is and will remain valid independently of my experience. For example, Galileo used a telescope to observe the points of light moving around Jupiter in different constellations. He was finally able to link these regularly recurring observations to the idea that they must be moons orbiting this planet. This insight, which Galileo was the first person to achieve, is not something that was bound to his person and his experience, like the response to the starry sky, which is somewhat different for each person, but rather a universal insight came to him that was already valid before his discovery and always will be. His person and his experience play no role in relation to the content of the insight. Here the high word of truth is appropriate, which stands above every person. For this concept of truth – in contrast to what is often used today, where it is considered possible for everyone to have “their own truth” – only makes sense if something exists that can serve as a standard for every person’s own search for truth. Assuming such a dimension of truth does not therefore exclude that there are different perspectives on truth; but what constitutes perspectivity as perspectivity, in terms of what it is relative to, can only be oriented towards an overarching truth, which one approaches better or worse. This ability to grasp something universal has to do with the level of the consciousness soul that takes us beyond our being a subject.

About the author:

Dr Jens Heisterkamp studied history, literature and philosophy, became acquainted with anthroposophy during his studies and worked with mentally handicapped children for several years parallel to his doctorate. Since 1995 he has been the responsible editor of the anthroposophical monthly magazine info3 and publisher in the associated Info3 book publishing house. He lives in Frankfurt am Main.

This article was originally published on the German website: Die Seelen-Lehre Rudolf Steiners