Diversity and Individuality in Jewish Mysticism

Author: Ronald Engert

In the Jewish mysticism of Kabbalah we find a hermetic correspondence of transcendence and immanence, of spirit and matter. The unifying element of these two spheres is the personal self, our individual soul identity, for God created man in His image. The diversity in the material world has its origin in the diversity of the spiritual world. Only the intention is different in both worlds.

MYSTICISM

“Oh taste and see that the Lord is good.” (Psalm 34:9) This tasting and seeing, spiritualized as it may be, is what the mystic is getting at. It is a certain fundamental experience of one’s self entering into immediate contact with God or metaphysical reality that determines the attitude of the mystic.

The word ‘mysticism’ comes from the Greek ‘myein’ = ‘to close one’s eyes or lips’, thereby shutting out external perception and coming to inner experience. Mysticism refers to one’s personal spiritual experience of a higher reality, commonly understood as God, Goddess or Divine. This experience is not predominantly rational. It is primarily emotio-spiritual, but can manifest in all five levels of the human being: Body, Emotions, Mind, Soul, and Sexus. A mystical experience can be had in all of these areas. It does not exclude the mind as a rational entity. Contemplative immersion in thought about certain aspects of reality, such as time, the self, eternity, meaning, or examination of sacred scriptures can produce an enlightenment experience. Predominantly, however, such an experience occurs through service, meditation, or ceremony.

TRANSCENDENCE AND IMMANENCE

The philosopher Walter Benjamin, of Jewish origin and blessed with deep mystical experiences, transferred Jewish mysticism for philosophical explanation of this world. He therefore built a bridge from transcendence to immanence. Moreover this made it possible for him to discover in the world the same principles that the mystics report in their description of the spiritual worlds. That is why he spoke of the “profane enlightenment” (cf. Benjamin, GS II, p. 297). Benjamin extended enlightenment, originally reserved for the mystic concerned with transcendence, to the earthly world.

Both transcendence and immanence coincide to form a unified reality.

Benjamin thus overcomes the classical split into spirit and matter.

Scholem speaks of the mystical moment in the continuation of his definition: “Is, after all, the symbol (…) a ‘momentary totality’ that is grasped in intuition, in the mystical moment, as the dimension of time appropriate to the symbol” (Scholem, p. 30). Benjamin speaks of the “now of recognizability” (Benjamin, GS I, p. 682 / GS VI, p. 46 et al.). It is the same motif.

The mystical cognition takes place in real time,

“every minute for sixty seconds” (Benjamin, GS II, p. 310), not separated from time.

THE MYSTICISM OF THE MERKABA IN KABBALAH

In the Merkaba-S. so Scholem, “we find here nothing of a unio mystica between God and the soul. Always the consciousness of the personality, of the otherness of God remains clearly preserved, yes, it is even exaggerated here! But also the person of the mystic does not lose its contours, not even in the highest ecstasy. Creator and creature face each other unmixed. […] He who in ecstasy has passed through all gates, has passed through all dangers, stands before the throne, who looks and hears …” (Scholem, p. 60).

The ancient Merkaba mystics saw God as an exalted king at a great distance. Only later did he move closer to the world and assume the character of immanence. Thus Rabbi Eleazar of Worms wrote in the 13th century, “God is everywhere and sees good and evil. Therefore, when you say prayers, gather your mind, for it is the saying, ‘I always confront God with myself’; hence the beginning of all Benedictions is, ‘Praise be to you, God’-somewhat like a man speaking to his friend.” (Sefer Rasiel, bl. 8b; cf. Scholem, p. 117) Here a relationship with God is expressed as with a friend, living from God as a counterpart, a Thou.

This exchange is ecstatic and divine. It is capable of enlightening the soul and revealing to it its true destiny.

The Jewish tradition of Kabbalah consequently developed this diversity in the core of its philosophy. Such as the Jewish theologian Martin Buber with his “Dialogic Principle: I and Thou,”. Or the Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas with his philosophy of the Other.

THE SEFIROTH IN KABBALAH

“The Divine Self,” writes Arthur Green in the preface to the Pritzker edition of the Sohar, “as perceived in Kabbalah, is the interaction between these seven forces or inner directions. In the same way, every human person is also God’s image in the world. The sacred structure of the inner life of God is also called the ‘mystery of faith’ in the Sohar, and is refined again and again by the Kabbalists through the centuries in countless images. ‘God,’ in other words, is the first being that springs from the divine womb, the primordial ‘being’ that takes form to the extent that the infinite energies of the Ein Sof begin to coalesce.” (Matt, Sohar, XLVIII)

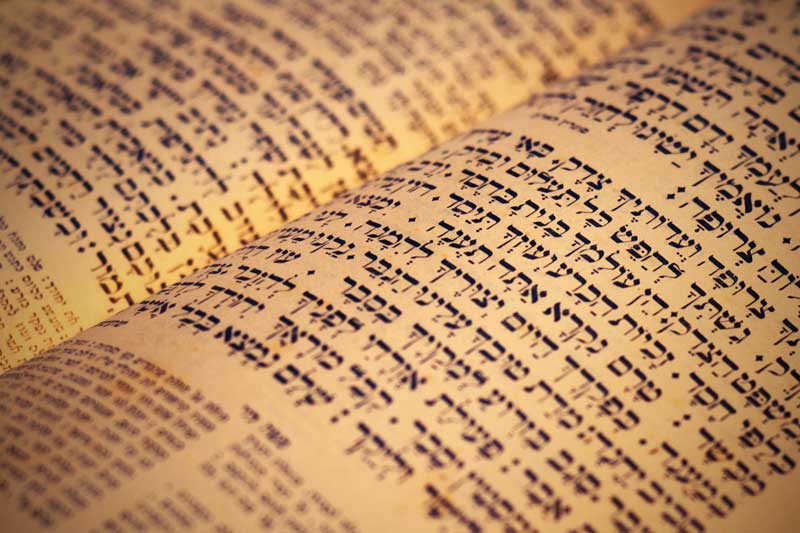

© Adobe Photostock

The seven forces here are the fourth through tenth sefiroth, which arise from the third sefira, Binah, which is understood to be the womb or feminine principle. The first sefira, Keter, is the first stirring of an intention within the Ein Sof, the Infinite. Keter is the crown, the personification of a royal identity, the highest manifestation of the spiritual body, both God and soul. Keter also means circle. In the Sefer Jezira, a 2nd century mystical scripture of Judaism, the sefiroth are described as great circles “whose end is embedded in their beginning and whose beginning is embedded in their end” (ibid., XLVII, cf. Sepher Jezira 2:4).

Thus, Keter, as the highest sefira, also completes a circle with Malkuth, the lowest sefira, where above and below are the same. So Keter represents God and Malkuth represents the Shekhina, the goddess in Kabbalah. In this way, the ten sefiroth also form the sacred marriage of goddess and god, Hieros Gamos. From Keter emerges Chochmah, the second Sefira, “the first and finest point of a real existence” (ibid., XLVII). Chochmah is the sacred wisdom, which is masculine as the counterpart of the feminine Binah. This is the first triad. The second triad begins again with God, and folds out into the seven other sefiroth.

About the author

Ronald Engert, born 1961. Studied German, Romance languages and literature, and philosophy, later Indology and religious studies at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt/M. Co-founded the journal Tattva Viveka in 1994, publisher and editor-in-chief since 1996. 2017 Bachelor’s degree in Cultural Studies at the Humboldt University of Berlin. Currently writing his master’s thesis on mystical language theory. Author of “Good That I Exist. Diary of a Recovery” and “The Absolute Place. Philosophy of the Subject”.

Ronald Engert, born 1961. Studied German, Romance languages and literature, and philosophy, later Indology and religious studies at the Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt/M. Co-founded the journal Tattva Viveka in 1994, publisher and editor-in-chief since 1996. 2017 Bachelor’s degree in Cultural Studies at the Humboldt University of Berlin. Currently writing his master’s thesis on mystical language theory. Author of “Good That I Exist. Diary of a Recovery” and “The Absolute Place. Philosophy of the Subject”.

Blog: www.ronaldengert.com

This article appeared originally on the German Homepage of Tattva Viveka: Das personale Selbst